The megastar is overcoming rejection—on horseback, no less—and inviting Black women to own their multidimensional identities right alongside her.

After releasing seven industry-defining solo albums, selling out stadium tours, launching multi-million dollar businesses, sustaining a power-couple marriage, and raising her own children, Beyoncé’s latest album surprisingly opens with her in a place of rejection and heartbreak. Cowboy Carter’s first track, “Ameriican Requiem” intimately reveals an icon moving through the grief of exclusion. Over a sonic deluge of triumphant guitar strings and powerful gospel riffs, Yoncé croons, “Used to say I spoke ‘too country,’ and the rejection came, said I wasn’t country ‘nough. Said I wouldn’t saddle up, but if that ain’t country, tell me what is?” She’s notably referencing the 2016 Grammy committee’s decision to reject “Daddy Lessons” from eligibility into the awards’ country categories, and the backlash she received for performing at the CMA Awards. On “American Requiem,” Beyonce lyrically takes aim at her latest round of critics, the gatekeepers of the country genre, while also making it clear she never needed their validation to begin with. She’s “the grandbaby of a moonshine man, Gadsden, Alabama. Got folks down in Galveston, rooted in Louisiana,” she explains, proving her roots are right in the heart of Dixie Land.

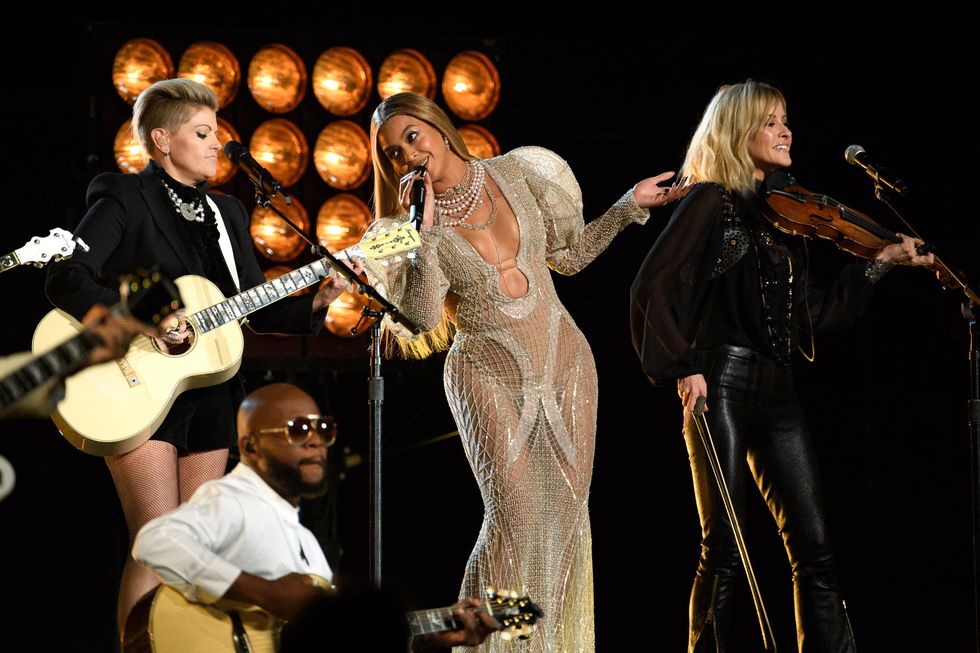

IMAGE GROUP LA//GETTY IMAGES

Beyoncé performs with The Chicks at the 2016 CMA Awards.

The reality is, the only force that could attempt to keep a country girl like Beyoncé out of country music is racism, and Beyoncé has the perfect response to that evil: vanquish it with the strength of her own God-given talent. It starts with even reclaiming the name Beyoncé for her bloodline, which was actually the maiden name of her mother, Celesine Beyonce (known to us as Tina Knowles). The name was misspelled Beyince on a few of their family members’ birth certificates, and doctors refused to change the name back because they were Black, according to Beyoncé’s mother. Little did they know, the name Beyoncé would become a household staple just one generation later. Fittingly, Beyoncé rocks a “Beyince” pageant sash on the cover of Cowboy Carter, calling attention not only to the name that was denied her people, but also to the genre she was locked out of. In 27 tracks, Beyoncé invites us into her American Dream, where Black women are free to own the multidimensionality of our identities right alongside her. Beyoncé is churchy, country, and cunty, and her audacity to define herself with all those seeming contradictions is real freedom.

KEITH GRINER//GETTY IMAGES

Brittney Spencer.

JASON KEMPIN//GETTY IMAGES

Tanner Adell.

But freedom isn’t freedom unless you’re willing to take others right along with you. In true benevolent queen fashion, Bey took her rejection from the industry and transmuted it into many seats at the table for other Black country artists. Tanner Addell, who is featured on “Blackbiird,” a remake of the classic 1968 Beatles song, said that Beyoncé’s announcing plans for a country-themed project positively influenced streams on her own songs. On February 20, Addell said in a TikTok her songs “Buckle Bunny” and “Love You a Little Bit” saw a 188 percent increase in streaming activity that month, after Beyonce’s “Texas Hold ‘Em” made history as the first song to top country’s Billboard charts by a Black female artist. Other prominent country voices and artists featured on Cowboy Carter include Brittney Spencer, instrumentalist Reyna Roberts, Tiera Kennedy, and banjoist Rhiannon Giddens.

While holding it down for the modern country girls, Bey also pays homage to the old guards of the genre by including stars like Willie Nelson and Dolly Parton on the album. Sure, you can try to lock Beyoncé out of country music, but what about Dolly Parton? No way. Parton makes her debut on Cowboy Carter during an interlude leading into Beyonce’s raw and scorching rendition of “Jolene.” “Ya know that hussie with the good hair you sang about? Reminded me of someone I knew back when, except she has flaming locks of auburn hair,” Dolly says in her comforting Southern twang. In Beyoncé’s take on the 1973 track, she personalizes the lyrics to include “I’m still a Creole banjee bitch from Lousianne.” While Dolly never quite said those words, by her own admission, Beyoncé’s mental tussle with Becky is not too different from her own rumble with Jolene. “Just a hair of a different color but it hurts just the same,” Dolly says. In one brief 22-second interlude, Beyoncé joins together not only generations of country, but also women from every cultural background. Any woman can relate to the fiery rage of seeing your man with another woman, okay?

Beyoncé includes another classic voice in country, Linda Martell, on the interlude The Linda Martell Show right before the album bounces off to the musically energetic track, “Ya Ya.” Linda Martell (née Thelma Bynem), is a Black woman from South Carolina who had a country single on the charts in 1969, but was still subjected to racist heckling down South by fans who only wanted to see white faces on stage, she told Rolling Stone in 2020. Now, the 82-year-old hands Beyoncé the baton and assists her in defining the genre she has now reclaimed for herself. Linda’s voice is introduced shortly after sound effects of applause and whistles (a vast departure from the boos and racial epithets Linda faced in her early days). “Ladies, and gentleman, this particular tune stretches across a range of genres, and that’s what makes it a unique listening experience,” Linda says, before the opening of “Ya Ya,” a bumping, funky, dance tune that paints a picture of Beyonce’s ideal America: one that is filled with ass shaking and Beach Boys-level good vibrations. Sounds like a good time to me. And the best thing about a Beyoncé party is that everyone, in all their fullness, is invited, too. An All-American hoe-down that no soul can be barred from—that’s a grace Beyoncé gives America as a sonic olive branch of forgiveness, even if the same Southern hospitality wasn’t granted to her just a few years ago.

MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES//GETTY IMAGES

Linda Martell circa 1969.

In Cowboy Carter, we witness Beyoncé make lemonade out of rejection by shattering the very box the henchmen of country music tried to imprison her in. The album, which is not a country album, but a Beyoncé album (as the queen said herself), unleashes another layer of the Houston native’s multi-dimensionality into the world, and she invites us to embrace our range right along with her. Pulling influences from Blues, Jazz, R&B, Country, Opera, Hip-Hop, Funk, and at times cathedral-level orchestration and vocals, is a way Beyoncé shows reverence for her own multi-cultural ancestry as a Black woman from the South with Creole blood. Cowboy Carter is as much of a musical melting pot as Beyoncé is, as this very country is. How fitting it is for her to share with us how she holds the expanse of American music and American history peacefully in her own body. We all need to take notes. At a time when the real history of this country is being ripped out of libraries and burned in flames, Beyoncé reclaims sovereignty over the one power Black folks have had since the beginning of time: our storytelling. And the story of us begins with defining ourselves, even when folks tell you that you don’t fit in where you belong.

In “Protector,” a track featuring Beyoncé’s younger daughter, Rumi, Bey belts out a soothing porch lullaby about legacy: “There’s a long line of hands carrying your name,” she sings. Cowboy Carter is an ode to all the forgotten and suppressed names that carried her own family, from Southern slavery to American pop idol status. With her unprecedented work ethic and divine-level gifts, Beyoncé has ensured that her children will never be excluded from owning the fullness of their own identities as Black people from the South the way she was. One of many generational curses, broken. From protective porch mama bear to alien superstar, Beyoncé owns all of herself, and if that’s too much for mainstream culture to swallow, they can choke. As a Black woman with southern roots myself (my grandparents are from Mississippi and Georgia, respectively), in the last few years, I’ve learned to embrace the wide expanse of my identity, too. After spending the majority of my adulthood in L.A. and NY, I’ve opted to slow down and spend the last few months in my native Ohio, mesmerized by the edgeless empty fields and thick forests. I hear folks from the coast often tease country folk, saying, “There’s nothing to do there.” Well, I’ve learned for myself that wisdom is born from the country because something about the infinite space gives the mind room to roam big. It’s from this same tradition Beyoncé’s creativity was drawn. It’s about time folks understand that the southern drawl holds the language of the past and the future.

Source link